A History of Sharrington / Norfolk Geology

There lies beneath Norfolk a platform of very ancient rock. In some places, this rock is about 1,000 metres below the surface and is similar to surface rock found in Wales and the Pennines, but, in Norfolk, this is overlaid by sediments which have accumulated over millions of years.

The most extensive sediment is the Chalk, in fact, virtually the whole of Norfolk is underlaid by chalk with the associated Flint, in some places to great depth. This means, of course, that, at one time, Norfolk was at the bottom of the sea.This time was during the Cretaceous Period, 190 to 136 million years ago.

On top of the chalk bed there are several other deposits of material caused by, at least, four Ice Ages. For example the last ice age, which reached its maximum extent 18,000 years ago and retreated about 10,000 years ago, is believed to have deposited the sand and gravel forming Salthouse and Kelling Heaths, where evidence has been found of Mesolithic Man.

In the (old) Sharrington Parish, which stretched North to the boundary with Saxlingham, there are found three types of earth. The northeast corner of the parish is part of the Cromer Ridge, where a thin loam covers sand and gravel. The eastern edge of the parish is touched by a Chalk Scarp, where the dirty white chalk is very close to the surface. In the rest of Sharrington, that is, the main part of the village and parish, the chalk bed is covered by the “Boulder Clay” as is much of central Norfolk. This is a stiff gray glacial deposit, rich in chalk stones, the flint. This clay subsoil is impermeable and supports a “Perched Water table”, that is, the water cannot drain through the clay to the chalk and is, therefore higher and nearer to the surface than it would have been had not an Ice Age glacier deposited the boulder clay. The most common top soil is dark, flinty and sandy Clay Loam.

During the Ice Ages, the land periodically rose and fell raising and lowering the sea levels. At one point after the last Ice Age, the southern part of the North Sea was converted into land, thereby joining Norfolk to Continental Europe and the so called “Maglemose” people migrated from Denmark into Eastern England. A Maglemosian settlement has been found at Kelling Heath. Also, fossils of Sabre Tooth Tiger, Elephant and Hippopotamus have been found in the Cromer area, showing that the climate had been much warmer at some time.

Source References :

(i) “An Historical Atlas of Norfolk” Published by the Norfolk Museums Service.

(ii) “British regional Geology. East Anglia”. Fourth Edition. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

The New Stone Age

The period following the Ice Ages brought Neolithic or New Stone Age Man to the area and, there is plenty of evidence of settled communities in North Norfolk, stone axes having been found in Thornage and Saxlingham Parishes as well as other places. It is not known whether stone age implements have ever been found in Sharrington, but flint chippings have been found here, all with a “Bulb of Percussion which, it is believed, can only be formed by striking the edge of a flint core to manufacture a flint implement. It is believed that, during this period, farming began in East Anglia including the keeping of domestic animals.

The Bronze Age

Objects of copper and bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, were first introduced into Norfolk about 4,500, years ago. Round barrows, circular burial mounds favoured by Bronze Age people, are found nearly everywhere. The nearest round barrows to Sharrington are found in the parishes of Blakeney, Wiveton, Saxlingham and Thornage. Of course, in view of the extensive farming activities in this part of the country, many round barrows could have been ploughed away.

The Iron Age

Iron tools and weapons, sharper than bronze, first came to Britain from the Continent of Europe, but, by about 650 B.C. were being made locally. In 54 B.C. Julius Caesar raided Britain with his legions from Gaul. In his writings, he listed the “Cenimagni” as being a tribe which he had encountered. This was more probably “Iceni Magni”, The Great Iceni, and the name Iceni was recorded in the first century A.D. The distribution of their coins indicate that their tribal area covered Norfolk, Suffolk and part of Cambridgeshire. As well as Caesar’s incursion, all was not peaceful in the area, as is shown by five large forts, with massive earthworks, at Holkham, Warham, South Creake and Narborough, which form an arc around Northwest Norfolk. The fort at Warham is not far away and is certainly worth a visit, and is free.

Reference: An Historical Atlas of Norfolk.

The Roman Occupation

In A.D.43, The Emperor Claudius, or more properly “Tiberius Claudius, Caesar Augustus, Tribune, Imperator, Pontifex Maximus, Pater Patriae”, ordered his Legions to invade Britain. They gradually fought their way through the country, building roads and forts, eventually pacifying most of the country, but never the north of, what was to become Scotland. They suffered setbacks, the most famous of which occurred in A.D.60 when, by mistreating the Iceni and its Queen Boudicca, the tribe revolted against the occupiers, who had sent most of their best troops to conquer and settle the tribes in the West, (Wales). Boudicca led her horde against the Southeast, sacking and burning Camulodunum (Colchester), Verulamium (St. Albans), and Londinium (London). However, the Legions were recalled and, unfortunately for them, a tribal militia or warlike horde was no match for a highly trained Roman Army and the Eastern Region was again pacified.

There then followed over three centuries of rule by Rome. In Norfolk, they built roads, towns and settlements. Apparently, there was a Roman settlement at the edge of Bale, bordering the parish of Sharrington. Towards the End of the Occupation. The Roman Army had always employed Auxilliary Troops to bolster its fighting strength and in Britain, many of these troops were from the Germanic Tribes across the North Sea. As the Empire declined through civil wars and invasions, raiding parties from the North European coast started to trouble the eastern and southern coasts of Britain and a series of defences were erected on the coasts of Britain, which became known as “The Forts of the Saxon Shore”. The fort at Burgh Castle near Great Yarmouth is in a well preserved state.

The Emperor Constantinus (Constantine The Great) by the Edict of Milan A.D.313 declared Christianity to be the official religion of the Empire, putting an end to the persecution of Christians. However, in A.D.410, the Emperor Honorius withdrew the last of the Legions from Britain. This left the Britons without a Standing army and opened up the country to the worshippers of WODEN.

References : An Historical Atlas of Norfolk and General History.

The Coming of the English

For the year 449, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle says “—-in their days, the Angles were invited here by King Vortigern, and they came to Britain in three longships landing at Ebbesfleet. King Vortigern gave them territory in the southeast of this land on the condition that they fight the Picts. This they did and had victory wherever they went. They then sent to Angel, commanded more aid, and commanded that they should be told of the Briton’s worthlessness and the choice nature of the land. They soon sent hither a greater host to help the others. Then came the men of three Germanic tribes; Old Saxons, Angles and Jutes…Of the Jutes come the people of Kent… Of the Old Saxons come the East Saxons(Essex), South Saxons (Sussex), and West Saxons (Wessex). Of the Angles… come the East Anglians, Middle Anglians, Mercians, and all the Northumbrians…“.

Although written about three hundred years after the event and there is no way of verifying the details, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle does attempt to describe how an historical fact occurred, namely, that the English did arrive on these shores and did, over a period of years, eventually overcome any resistance, conquer and call the land England, driving any who still opposed them into the hills of Wales. According to the Ordnance Survey Map, “Britain in the Dark Ages”, this whole area was known as “East Engle”, the district being eventually divided into Norfolk and Suffolk, (Nordvolk und Sudvolk), the North People and the South People.

Wherefrom did these people come? The Jutes from Jutland, the main peninsula of Denmark. The Angels from Angeln, Germany south of Denmark, (Schleswig Holstein) and the Saxons from Lower Saxony on the North Sea coast between the River. Elbe and The Netherlands, but they also, probably, included Frisians from islands off the north coast and other tribes. In the museum at Schleswig, a town in North Germany, there is a very well restored Long Ship of the type used by the Anglo Saxons to row across the North Sea. Not only did the Anglo Saxons fight the Britons and Picts in this island, but they also fought each other in seemingly never ending wars of rivalry between the Kingdoms which they created.

Christianity

For the year 596, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle says, “Pope Gregory sent Augustine to Britain, with a good many monks, who preached the Gospel to the English People”. Over a period of years, they gradually converted the English. This probably meant that once a King was converted, he would declare his Kingdom to be Christian. And so came “Getterdammerung”, The Twilight of the Gods, but not entirely forgotten in the English Language. Sunday, Sunnan daeg, the day of the Sun, Monday, Monandaeg, the day of the Moon. Tuesday, Tiwes Daeg, Tiwes, the God of War, Wednesday, Wodnes Daeg, Woden, The King of the Gods. Thursday, Thors Dagr, The Hammer God of Thunder and Lightning. Friday, Frige Daeg to the Great Goddess. Saturday, Saeternes daeg, to Saturn. It is interesting to note that all the above Gods are Old English (Anglo Saxon) except Thursday, Thors Dagr. Thor was the Scandinavian version of the Germanic god “Donner” (Donner und Blitzen, Thunder and Lightning) and obviously came with the later Vikings.

The Vikings

For two hundred years there had been no significant attacks from the sea, but in 793, “On January 8th., the ravaging of Heathen Men destroyed. God’s Church at Lindisfarne through brutal robbery and slaughter”. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle goes on to say, “836, King Ecgbryht fought with twenty five ships’ companies at Carhampton, and there was great slaughter, the Danes held the battlefield”. “In 870 The Force went over Mercia to East Anglia. In that year, St. Edmund, the King, fought against them and the Danes took the Victory, killed the King and overcame all the land. They destroyed all the churches they came to; the same time they came to Peterborough, they burned and broke, killed the Abbott and monks, and all they found there”. So died the King of East Anglia, Edmund, after whom St. Edmund’s Bury, or Bury St. Edmunds is named.

Thus began over two hundred years of Viking attacks, and eventually, Danish Invasions, until half of England was overun and known as “The Danelaw”. Denmark, in those days, was much larger than it is today, and included parts of other Scandinavian countries. King Alfred held them from conquering Wessex and King Eathelred paid them Danegeld to try to keep them quiet, but, in 1013, King Sven Forkbeard, son of Harald Bluetooth, landed here and within a year had been accepted as Full King.

In 1016, King Sven’s son Cnut “received all the Kingdom of England”. Thus, King Canute was King of Denmark and England. During these times,. East Anglia including of course Sharrington, was well within the Danelaw. During the Anglo Saxon Danish period, Sharrington is known to have been a settlement. But more of that later! In 1066, King Edward the Confessor died and Harold Godwinson, of Danish descent, was proclaimed King. In that year, he fought and defeated a Norwegian invasion under King Harald Hardrada, in Yorkshire. But, while this was going on, another threat was brewing in the south.

1066

During the years of the Viking Raids and invasions, not only was England attacked but also the Continent of Europe and, in France, to such an extent that a large part of Western France was ceded to The Northmen, which became The Dukedom of Normandy. In 1066, The Duke of Normandy was William and, by this time, he and his countrymen spoke French and lived in the French style. William claimed that Edward the Confessor had made him heir and that he was the rightful King of England. With a favourable wind he sailed with his army of Normans and French, landing on the south coast of England. Meanwhile Harold, having defeated the Norwegians in the North, made his way South with what was left of his army. They met at Battle in Sussex, Harold was killed and his army was defeated. William, after fighting and slaughtering his way round England, was crowned King.

References: The Anglo Saxon Chronicle and General History.

William then began replacing the Anglo-Saxon-Danish landowners and Senior Clergy with his own henchmen and followers, creating a new aristocracy, which spoke French. The Conquest and then English Revolt gave the Normans the chance to change society and by 1086 scarcely one percent of the Saxon Landowners, though innumerable Saxon tenants, remained. The free villages of East Anglia were subjected now to Norman Lords.

The Domesday Book

In 1086, fearing a Danish Invasion and requiring taxes to pay for defence, William sent out four circuits of leading Magnates with Latin speaking scribes to take stock of the country and value everything worth anything. By 1090, this information had been compiled into the Domesday Book. This book gave a double picture, the country as it had been in King Edward’s day, before 1066, and as it was twenty years later. Thus, we have our first written account of Sharrington, given as Scarnetuna and Scartune.

Scarnetuna or Scartune

In King Edward’s day, the village belonged to Fakenham and consisted of One Carucate of land, as much land as a team of oxen could plough in a season. It had nine Borderers (smallholders), one Plough in Demean, for the Lordship, and one for the tenants. It had 30 sheep. Three Socmen (freemen) held six acres. It was seven furlongs in length and six in width, paying ten pence in tax. A penny was a small silver coin.

In 1086, the village and surroundings had been transferred to the King’s Manor of Holt. One Freeman, “Ketel” had lands, which on the death of King Edward were added to the “Beruite”? This is the first name of a resident that we have. Scartune now consisted of two carucates of land (doubled in size), there were eight Socmen and six Smallholders. Now it had sixty sheep. The value of the Beruite of Scartune in King Edward’s time was 20 shillings. In King William’s time, 40 shillings.

Add to these 14 men, wives, children, old folk and Villeins, who had been slaves, plus their wives and families. We then have a reasonable idea of village life at the time, but it would be impossible to guess at a figure for the population in 1086. The Shepherds were probably villeins and the sheep owners, Socmen.

References:

(i) A History of England, 1966, Redwood Press Ltd.

(ii) A translation of the Domesday Book.

(iii) Chamber’s Dictionary.

A translation of the word “Beruite”, as in The Beruite of Scarnetuna is not easy. It is not a Latin word and is not an Old English or Anglo Saxon word. In modern French, a berger is a shepherd and ruite could be old French for. La route, so, perhaps, Beruite could mean “Shepherd’s Way?

Scarnetuna,Scartune, (Sharrington)

Travelling with the four circuits of Magnates who gathered the information for Domesday Book were Latin Speaking Scribes probably priests, who compiled their lists in Latin. The Domesday Book is written in abbreviations. As can be seen, the spelling of Sharrington is given in two variations, SCARNETUNA and SCARTUNE. We could probably discard the letter “A” at the end, which merely gives the Latin feminine form of a proper noun. Other nearby villages are given as Huneworda (Hunworth), Stodiea (Stody) and Glaforda (Glandford).

In the Sharrington Church Guide, the translation of Scanetuna is given as “Muddy Place”. An alternative given is to do with “Sharming Bees”, and even the village sign shows a beehive and, below, a Tun (barrel). The first of these hypotheses is derived from a publication translating Domesday names into modern English. Scarnetuna is given as derived from Old English (Anglo Saxon) “Scearn Tun”, Muddy Tun. The second seems to be pure speculation and, certainly, the Tun in this case, had nothing to do with a barrel. There could be another possibility for the translation of Scarnetuna.

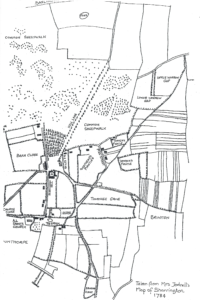

According to An Historical Atlas of Norfolk, the northern part of Sharrington Parish was Common Land and remained so until 1797, when it was enclosed and parcelled out to land owners. Common Land belonged to everyone and was generally used in olden times for the grazing of domestic animals. This Common Land extended North from what is today The Street, all the way to the border with Saxlingham Parish. This Common was variously known as “Sharrington Common” or “The Common Sheepwalk” and it bordered Dalling Common on the West. This information is shown on a map dated 1784, prepared by a Mr. C. Bell for the landowner of the estate of Sharrington, Mrs. Eliz. JODRELL. (See Appendix).

We have seen from. the Domesday Book that, in 1086, the village owned 60 sheep and, being common land, no doubt the surrounding villages also grazed their sheep on Sharrington Common Chambers (Cambridge) Dictionary gives “Sceap” as Old English for Sheep and “Sceran” as Old English for TO Shear. Schar is Germanic for Flock and Scharf for Sheep. These words could all be from the same source. Under the entry for Town, the Old English was “Tun”, originally meaning enclosure from the Germanic “Zaun”, pronounced “TSOWN”.

According to An Historical Atlas of Norfolk, town and village names fall into certain categories and examples given include “Ham” and “Tun” places. Those names ending in Ham were generally more important than those ending in Tun. For example, Fakenham and Sheringham. Sharrington is a Tun village, as are Brinton, Briston etc. In certain old documents, Sharrington is referred to as “This town”, obviously referring to the old “Tun” ending of the name. One hypothesis is that Tun villages are thought to be named after either the village chief or the use to which the village was put. So Sharrington could have been “SCERANTUN” to the Anglo Saxons, meaning Shearing Enclosure. This is more likely as, on Mrs. Jodrell’s Map of 1784, on the southern side of the street, the map is marked “Shepherds Pightles”. A pightle was a small enclosure or croft.

Call it what you will, Muddy Place, Beehive Village, or Sheep Shearing Enclosure, but the constant references to sheep and the stone sheep’s head in the church cannot be ignored. Also, bear in mind that, in the Middle Ages, East Anglia became rich from the export of wool. In “A History of England” it is stated, “Norwich, second city of the Realm, controlled export from dozens of the villages…”Including Worstead (and other places) which gave their humble names to cloths…whose wealth flowered in tall churches and solid houses”.

All Saints Church, Sharrington.

The church, as we know it, did not exist in 1086, Domesday, the nearest churches in the Hundred of Holt being at Saxlingham and Thornage. These churches were, obviously, Pre- Conquest, such churches being generally known as Saxon Churches. This does not mean that there was no place of worship in Sharrington. Probably, an insignificant little building was not worthy of mention. In the sixth century, when Augustine was sent by the Pope to convert the English, he instructed his followers to site the new places of worship on the old Pagan sites, where they had always worshipped their gods. The site of All Saints Church could have been a place of worship for a long, long time.

The present building of All Saints Church would seem to have commenced in the late 13th: century and was able to accept its first Rector, Simon de Morton, in 1323. Of course, being a Norman French Roman Catholic Priest, conducting the Service in Latin, it is doubtful whether many of the congregation understood any of it, but they would have been taught the responses by rote. The Bible was first translated into English in 1380, but, even then, the services continued to be held in Latin. Building work continued, and the church tower was constructed, mainly in Flintstone, as was the rest of the building, later in the 14th. Century. The interior walls of the church would have been decorated with colourful religious paintings.

The Norman Aristocracy in Sharrington.

As stated in the Domesday Book, Sharrington became part of the King’s Manor of Holt and all taxes would have gone to the King. If there had been a previous Saxon Lord of the Manor, he is not mentioned. When William became King of England, he did not relinquish his Norman and French possessions and, in the following years, this was the cause of almost continual warfare in France, as his successors defended or tried to extend their extensive holdings in France.

When Stephen became King in 1135, his succession was disputed and a terrible civil war and anarchy ensued in England between Stephen and The Empress Matilda, the widow of the German Emperor and her son Henry of Anjou, exacerbated by disaffected barons. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle says:- “for the land was all ruined with such deeds; and they said openly that Christ slept, and his saints.” On the death of Stephen in 1154, Duke Henry became Henry II of England.

It is presumed that Sharrington’s taxes continued to be paid to the King until the Civil War but, in 1219, during the reign of Henry III, Hamon Fitz Peter was “Petent” (Patent?, Patentee, one who holds a Patent, an official government document) and Gregory de Sharenton, “Deforciant” (one who resists an Officer of the Law in the execution of his duty), were involved in some legal proceeding, which resulted in a fine being levied on Sharenton.

In 1228, Peter de Sharington (note the change of spelling) “conveyed lands to Oliva,. daughter of Alan, son of Jordan,and it appears that these. Lordships were, in this reign, in the Earls. of Clare, who were the Capital Lords”. So it would appear that before or during the reign of Henry III, the ownership of Sharrington had changed. There was, obviously, trouble in Sharrington, in fact, there was always trouble between the Norman Barons and the King and, no doubt, these troubles filtered down to the poor shepherds, farmers and villeins.

Peter de Letheringset was Lord of the Manor in the sixteenth year of Edward I, 1288. John Dawbney de Broughton held the Manor “in 1323 presented to this church, and in 1327 as Lord of Scarneton or Sharington as the Institution Books testify”. This is the first we hear of the Daubney family, who, were to hold the Lordship of Sharrington for over two hundred years.

Source References:

(i) General History and The Anglo SaxonChronicle.

(ii) Copies of old documents, that referring to John Dawbney de Broughton headed “Dawbney. Harl. 1552, ink fo. 115, pencil 109.” (Whatever that means?)

Sharrington Hall.

This imposing and grand old building is now in private ownership, but it was obviously. built and lived in by the Lord of the Manor, but which Lord of. the Manor? As already stated, the Domesday Book does suggest by stating “one plough in demean for the Lordship”, that there was a Saxon.Lord, but Scarnetuna belonged to Fakenham, so maybe he lived there. We know that William took the village and land into his manor of Holt and that he cleared out the Saxon aristocracy. There may have been a pre-conquest building on the site, but, if so, it has either been demolished or it has disappeared into the fabric of the later building part of which looks very old indeed: Materials cannot be used for dating parts of the building, as it is mainly of Flint construction, which has always been used in this part of Norfolk and is still used today. It is believed that there are traces of a moat around the building and, if so, it would indicate that, at one time, Sharrington Hall was a fortified manor house.

It would appear that Thomas Daubeney extended the building to the west in the late 15th century, when it was known as Daubeney so it is obviously older than that, probably dating back to the 14th. century and maybe even to the late 13th. century, contemporary with the church building. The Norman Lord of the Manor needed a Manor House to live in, so perhaps the hall, in some form, is as old as the first Lord after the Beruite of Scatune passed out of the ownership of the King’s Manor of Holt. We hear of. Gregory de Sharenton, who was in some sort of trouble in. 1219, during the reign of Henry III, so maybe he built the first hall?. Sharrington Hall has also been described as an Elizabethan building, so perhaps it was remodelled or refurbished during the reign of Elizabeth I.

The Black Death

In 1348, the Black Death, or the Bubonic Plague, was carried to Italy from the east. It struck down the people of Florence, passed on to France and, in August, reached Weymouth. Early next year the pestilence broke on London and East Anglia, then crept northwards. Three Archbishops of Canterbury, 800 Norwich Priests and half the monks of Westminster died in a year. It bore hardest on the poor, with corn uncut and cattle wandering, but it spared none from a King’s daughter to an anchorite monk. It is estimated that the plague carried off one third of the population of England. We know now that the disease was caused by the bite of an infected rat flea but, then, a flea bite was an everyday occurrence, as it still was in the city slums of 1940, and nobody in those unhygienic times associated a flea bite with sudden death.

Wars and the Peasants’ Revolt.

During these times, the wars continued, with the Anglo-French King and Aristocracy trying to hold or regain their provinces in France. Three great battles are of note, Crecy 1346, Poitiers 1356, and later Agincourt 1415. The main reason for these English victories was that the French King relied on the chivalry of armoured Knights, whereas the English Kings, Edward III, his son, The Black Prince and later Henry V, held their cavalry back until the French Chivalry had been massacred by the Welsh and English archers, which was considered bad taste by the French. You would have thought that they would have learned their lesson after Crecy!

However, times were changing and the eventual ejection of the English from France had, probably, less to do with. Joan of Arc, who was burned as a witch in 1431, casting spells and leading French armies, but more to do with the introduction of firearms. All the great castles were built to withstand bow and arrow and knightly charge warfare. They were not much use against cannon shot and mortar fire, which could lob shells into the castle grounds and buildings. It is quite strange that, even in the eighteenth century, English Kings were still claiming, on their coinage, to be Kings of France.

Now, back to England. One consequence of the Black Death was that labour to work in the fields became scarce, and those villeins that were left became more aware of their own value and there was unrest as the lords and landowners tried to reimpose their old conditions on the workers.

In 1380, England was at war with four countries, France, Flanders, Spain and Scotland, and had lost both alliances and trade. The cost of all this was straining the middle classes, merchants, etc., who urged the government to impose a Poll Tax. At first, a peasant was only charged four pence, but, in 1381, the tax was put on each village an average sum of one shilling, to be paid by every soul over the age of 15. Payment was evaded on a large scale, so the government replaced local collectors with Sergeants at Arms, professional armed soldiers, who began a house to house census. Riots followed at once, Jurors and Clerks were killed in Essex and riots began in Kent, led by Wat Tyler.

The riots spread to East Anglia and Norfolk saw widespread unrest, one leader of the rebels being John Litser. There ensued killing and looting and there were incidents involving threats extortion and despoliation in the parishes of Bale and Hindringham. Rebels were known from Hindringham, Thornage and SHARRINGTON. Wat Tyler was killed in London. Bishop Despenser of Norwich rallied the gentry and ended the rebel’s resistance near North Walsham, John Ditser was summarily executed. Bishop Despenser was noted for his ruthlessness and determination. Churchmen did not just preach the Gospel in those days.

Reference: An Historical Atlas of Norfolk.

The 15th. Century and The Renaissance.

This is supposed to be the transition from the Middle Ages to a more modern world, following the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in the middle of the century and the spreading out of ideas from that city. However, the Renaissance probably did not make much difference for the ordinary folk of Sharrington or for the country as a whole. ‘Civil Wars broke out in England, the so called Wars of the Roses, not between Yorkshire and Lancashire as such, but between the Royal Dukedoms of York and Lancaster, to settle which member of the Royal Family would be King. Of course, the squabbles in France continued as well.

The Dawbney, Daubenye or Daubeney family were Lords of Sharrington and, in 1469, John Daubeney was killed by “shell shot” whilst helping to defend Caister Castle for the Paston Family against John Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk. John was a younger son of the Daubeney family and, in his Will, he left £6 for a Chantry Priest at Sharrington to pray for his soul in the church. (Presumably until the £6 ran out?). John Daubeney’s brass figure, in full armour with sword and spurs and with a Lion? at his feet, resides in All Saints Church.

In 1485, Henry Tudor put an end to the civil war when he defeated and killed Richard III at Bosworth Field. Henry VII is of particular interest to numismatists, as coin collectors like to call themselves, because he introduced the first “portrait” coins in England. Until then, the silver “hammered” coinage had merely portrayed a crude, crowned facing bust of the King, which did not look like anyone in particular, but, following the custom of the Renaissance Princes of Europe, Henry introduced Testoons, (shillings) and Groats, (four pence), showing a bust, which was an actual profile of his own face. The coins were still “hammered” however, as opposed to milled, pressed or machine made; which process had to wait until Elizabeth was on the throne.

References:

(i) General History,

(ii) All Saints Church Guide.

(iii) Seamy, Standard Catalogue of British Coins, Volume 1, Coins of England., and actual specimens. The reason that a reference to coinage has been made is that, in a following chapter there is a direct connection between coinage and the Daubeney family.

Henry VIII and The Reformation.

In 1509, Henry VII died and his son became Henry VIII. Everyone has heard of this Henry, who is arguably the most famous; or infamous King we have ever had. When he came to the throne he was, of course, a Roman Catholic, as his predecessors had been since Saxon times. He married an ardent Catholic, Catherine of Aragon, his brother’s widow, who bore him a daughter, Mary.

The Reformation is a complicated subject, but put simply:- There had been dissenters to the Catholic Religion before,but in 1517, a German Catholic Monk, Martin LUTHER, had become so disillusioned with the wealth and corruption of the Pope and Cardinals that he posted his 95 Theses on the Church door at Wittenberg. His main complaint seemed to be over the-sale of “Indulgences”, that is, you could buy-a piece of paper which absolved you from any sins that you may have committed. A new religion was founded, Lutherisch-Evangelisch-(Lutheran Evangelist). This started a new war in Europe Catholic against Protestant. Henry was still a Catholic and he wrote a book against Luther, which so impressed the Pope that he gave Henry a new title, “Fidei Defensor”, Defender of the Faith, a great joke, in view of what happened subsequently.

Henry was tiring of his wife, Catherine. She had produced a daughter, Mary, but other children had died and Henry wanted a son and heir. He had natural children with other women, but none but a Queen’s son could inherit the Kingship. He and his Cardinal, Wolsey, tried devious means to declare his marriage null and void, but the Pope, backed by Catherine’s influential relatives, would have none of it, so Henry decided to invent his own “Church of England”, with himself as its head. This had an added bonus for him as he began to sequester the wealth of Monasteries and Abbeys to pay for his extravagant lifestyle and his foreign wars; kicking out the monks and nuns. The clergy and important people had to accept Henry as head of the new church. The most famous person who refused was Thomas More, who had previously been a persecutor of Protestants and who was executed.

These must have been difficult times for the Lord of the Manor and Rector in Sharrington, as they were throughout the country. In 1527, Giles Daubeney was Rector under the patronage of Thomas Daubeney and, in 1533, Leonard Hadon became Rector under Henry Daubeney. In about 1529, King Henry had allowed the burning of a few Protestants but, by 1535, he was executing Catholic Friars after his excommunication from the Church in Rome. He cast off his wife Catherine, married Anne Boleyn and so, in 1533, Princess Elizabeth was born to Protestant parents.

Also in 1533, Thomas Hunt became Rector of Sharrington under Henry Daubeney, and he continued as Rector until 1554. So, Hunt and Daubeney. became Protestants, together with their church, whether they wanted it or not. No doubt, the residents of Sharrington were as confused about the new religion foisted on them as were the Rector and the Lord of the Manor. Luckily, the North Sea intervened between England and the mainland of Europe, otherwise the Wars of the Deformation would have spread here. It is known, from An Historical Atlas of Norfolk, that sometime subsequently, a Recusant Catholic Priest visited Sharrington, no doubt to celebrate the Mass with secret believers in the old religion.

William Sharrington.

It would appear that, during the later years of Henry’s reign, there was serious trouble in the Daubeney family. William Daubeney, also known as William Sharrington, who was the third son of Thomas and brother of the Sharrington Lord of the Manor, Henry Daubeney, held various positions at court. In 1539, at the dissolution of ‘the monasteries’ and abbeys, William Sharrington purchased Laycock Abbey for £738. However, in 1549, after nefarious dealings with the coinage in collusion with Lord Thomas Seymour, Treasurer of the Mint, both men were arrested. Sharrington confessed, blamed Seymour, who was beheaded, but escaped himself with an attainder and forfeit of lands. Sometime later he regained all his land including Laycock Abbey, on payment of £8,000. William Sharrington was later knighted at the coronation of Henry’s son, Edward VI. On Henry VIII’s third coinage and his posthumous coinage of Bristol, his silvercoins bear the mint mark “WS”, a monogram of William Sharrington.

These proceedings are typical of activities during the reign of ‘Henry VIII, who himself should have been arrested for interference with the coinage. In later life, Henry was known as Old Coppernose because he had so debased the coinage that, after constant use, his coins showed signs of wear and the base metal showed through the silver, turning his nose copper colour. But he was the King and could execute wives as well as many other people and could fiddle the Treasury for his own ends.

In 1547, Henry VIII died, leaving a son, Edward, from one of his wives, Jane Seymour, who he did not execute, but nevertheless died in childbirth. Edward VI was only a child when he became King. He was born a Protestant, but he was a sickly youth and died in his teens.

Source References:

(i) An article on Laycock Abbey and William Sharrington.

(ii) Seaby’s Coins of England.

“Bloody Mary”

In 1553, Mary, Henry’s daughter from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, became Queen of England. She, like her mother, was a fervent Catholic and became, known as Bloody Mary when she started burning Protestants after her marriage to Prince Philip of Spain, probably under his influence. She even burned Archbishop Cranmer and imprisoned her half sister Elizabeth in the Tower of London, as she feared an uprising to replace herself with Elizabeth. People were burned in East Anglia,- Sussex, Kent and London, including women and boys, the aged and blind and many others. No doubt William Manser, who was appointed Rector of Sharrington in 1554 by Sir Richard Southwell, was a Catholic. One interesting point about Mary’s reign is that, in1554, she had minted Shillings and Sixpences showing the heads of both Mary and Philip, with the titles. “Philip et Maria. D.G. Rex z Regina Ang.”, Philip and Mary, by the grace, of God, King and Queen of England. Philip was never actually crowned in spite of Mary’s wishes.

Elizabeth.

In 1558, Queen Mary died and Philip was back in Spain. So ended Spanish influence in England and the burning of Protestants. Mary’s half sister, Elizabeth, the daughter of Anne Boleyn, a fervent Protestant, ascended the throne, to the dismay of Catholics. In Sharrington, the Bishop’s Vicar General appointed Thomas Whitby as Rector. By this time, the ordinary farm workers and shepherds must have been completely confused over religion. In 1565, Christopher Daubeney, the last of the Daubeney name to be patron of the -church, appointed Nicholas Ruckesby as Rector. The Reverend Ruckesby would have been officially a Protestant Priest, but who knows, as Sharrington is known to have been visited by a Recusant Catholic. Priest at some time.

This was the time of Priest Holes, when secret rooms were prepared in large houses to hide recusant Catholic Priests. It is not suggested that here was ever a Priest Hole in Sharrington. Catholic troubles were at their height when Mary Queen of Scots, a cousin of Elizabeth who had been ejected from Scotland by Protestants, and under restraint in England, was executed for being involved in plots to usurp Elizabeth.

Christopher Daubeney, his Last Will and Testament.

The Daubeney family held the Lordship of Sharrington for over two hundred and fifty years. Various spellings of the name are given in different documents and sometimes in the same document, for example:- John Dawbney de Broughton; Daubney Gent; Barthilmew Dawbnie; John Dawbeney of Caistor; Robert Dawbany of Norwich;. etc. One of the last Daubeney Lords of Sharrington and certainly the last one as patron of the rector. was Christopher Daubeney, who died in November 1584 and whose Will is extant and worth quoting in full:

“1584 November 15. Christopher Dawbeney of Sharrington. Co. Norfolk, Esq. To be buried in the quier (sic)- of Sharrington Church amongst my ancestors. To the Poor of Sharington.20 shillings:- of Bale 10s:- and of ffielddalling (sic)10s:- to my wife Phillipe all my manors and lands in:. Sharington, &c.’in Co..of Norf. for life; remainder to my son Henry Dawbeney:- my sons Thomas, Clement and Robert. Agreement between me and Edmunde Gresham that if my son Henry Dawbeney and Mris, Anne Gresham marry, the said Anne shall have during the life of said Henry an annuity of £30 out of the above lands in Sharington during life of my wife: My daughter Frances Dawbenye £200:- My Water Mill in Sharington to my son Henry, and all my lands in Bale, Letheringsetti and ffielddalling. He to be my sole executor, My Friend Wm. Boyton, Dr. of. Physic, supervisor Witnesses, Wm. Lomnor, Thos. London, Nicholas Ringolde. Proved…Somerset House, 19 October, 1585.

From this Will, we learn that the Dawbeneys also owned, as well as in Sharrington, lands in Bale, Letheringsett and ffielddalling. When Sharrington was a an individual parish and not part of Brinton, Sharrington extended south down the hill into what we now think of as Brinton, though it is sometimes known as Lower Sharrington, through which runs a stream. This must have been the location of the Water Mill that Christopher left to his son Henry. There must have been a millpond and sluice, to regulate the water and turn the millwheel. In Mediaeval tithes, the Lord of the Manor always owned the local mill and farmers had to take their corn to the Lord’s mill to have it ground into flour, an extra form of taxation. The last Daubeney Lord of Sharrington we hear of is Henry, son of Christopher, who was probably the Henry Daubeney Gent., buried 3rd. August 1624 at St- Luke’s, Norwich. So , sometime between 1585 and 1601, when William HUNT was patron of a new rector, John Stallon, the Manor of Sharrington passed to the Hunt Family.

The 17th. Century.

In 1601, William HUNT was Lord of Sharrington. In 1603, The Great Queen Elizabeth died, to be succeeded by James VI of Scotland son of Mary Queen of Scots. James VI of Scotland became James I of England and, on his coinage, King of France, though it had long gone. This was another century of religious troubles with the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 by Catholic malcontents attempting to blow up the King and Parliament. It was also the century of Bartholomew LEGATE, the last heretic burned at Smithfield; the Witchfinder General, Civil War, the execution of a King, The Commonwealth of England, the Lord Protector, the Restoration of the Monarchy and the final, ejection of a Catholic King, James II, brother of Charles II.

In spite of some good intentions, life was often short and brutal during the 17th. century. In 1603, 38,000 Londoners died of the Pestilence, hygiene and sanitation was virtually none existent. Many people lived in hovels which were breeding grounds for fleas, bedbugs and lice. Childbirth deaths were common for mothers and babies. The roads were unsafe with highway robbers, often in league with innkeepers, running wild. Criminals were hanged in dozens and, during two years in the middle of the century, about two hundred so called “Witches” were executed in East Anglia alone.

Religion also stirred up troubles in the century. Although James I and later. Charles I were Protestants, there was a leaning towards the ornamentation of the Roman Church, which upset the Puritans. Luckily again, England was saved from the great wars of the Counter Reformation by the North Sea, when great armies under the Catholic Generals, Wallenstein and Tilly, and Protestant armies under Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, ravaged the continent for thirty years and decimated the populations of the German States in the name of Christianity.

The English Civil War.

This war, which began in 1642, was not another. Peasants’ Revolt. The King, Charles I, believed that he reigned by the auspices of Christ and his coins were stamped “Christo Auspice Regno”. This arrogance led him to impose laws and taxes without reference to Parliament. He was ostensibly Protestant, but his wife was a French Catholic. This caused a huge split in the country, with some aristocracy and gentry supporting the King, but with Parliament, also composed of aristocracy and gentry in firm opposition. King Charles raised his Standard, virtually declaring war on Parliament. The armies met at Edgehill, which was an undecided battle. O.Cromwell, Gent., from the eastern counties, returned home to form his own “Ironsides”, cavalry, and eventually the New Model Army.

Although in the two major battles, Marston Moor and Naseby, Oliver. Cromwell was not the Commander in Chief, he was, nevertheless, instrumental in causing the defeats of the King’s army. Whereas Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the King’s cavalry Commander, after charging through part of the Parliamentry Army, went chasing away after booty, Cromwell’s Ironsides, through strict discipline, charged through their enemy, but remained at the battle and charged again, routing the King’s Army. The war rumbled on and, eventually, the King was utterly defeated, captured and executed. Norfolk, during this time, was mainly parliamentarian, though there were some Royalist sympathisers. Luckily, there were no major battles or upheavals in this county, so families were not generally, “By The Sword Divided”. No doubt, some Norfolk men served in the New Model Army.

After the defeat of the King, a Commonwealth of England was formed but was so troubled by religious dissent between Protestant seats that Cromwell, who was by now, Commander in Chief of the Army, was forced to declare a Protectorship and declared himself Lord Protector, though he refused to be crowned King. However, England was not ready for revolution and, after Cromwell’s death, Charles II, son of the executed King, was restored to the throne. It is interesting to speculate on what the result would have been had these events occurred 150 years later, at the time of the American and French Revolutions.

Charles II also had his problems, what with The Great Plague of 1665 (People were still dirty and did not realise that Flea Bites could kill) and the Great Fire of London in 1666. Towards the end of the century, after Charles II died, his brother, James II, became King. James was a fervent Catholic and the fear of him trying to reintroduce Catholicism as the Religion of England led to his ejection from the country and the entry of the Stadtholder, William of the Netherlands and his wife, Mary. This was William of Orange, the “King Billy”, beloved of the Northern Irish Protestants after the Battle of the Boyne.

Religious Non Conformity

The. persecution of Catholic dissidents continued from the late 16th. century, when the penalty for not attending Church was 20 shillings a month. There was the death penalty for all priests ordained abroad, and imprisonment and, in some cases death for those who aided priests. Nevertheless, Catholicism remained alive and gained ground in Norfolk as elsewhere in the first decade of the 17th. century. Between 1600 and 1616, at least one Catholic Priest is known to have visited Sharrington. The upheavals in religious affairs led to the formation of Non Conformist Sects, mainly Independents, Baptists, Presbyterians and Quakers. Later, persecution of Protestant Sects increased until the Toleration Act of 1689 allowed freedom of worship in premises properly licensed for that purpose. There was a. Primitive Methodist Congregation in Sharrington and a Wesleyan Chapel was erected in the 19th. century, which is now privately owned.

The Poor Laws.

How did Poor people fare during these times? In 1598, after terrible trade recessions, and following the practice of towns like Norwich, Parliament passed an Act which became the basis of the Poor Law for two hundred years:

(i) Independence was upheld as being better than relief; parents and children; if able to do so, were legally bound to support each other, while refusal to work or to accept reasonable wages constituted Vagabondage.

(ii) Begging became illegal.

(iii) The able bodied vagabond should be set to work in the House of Correction, or the Gaol.

(iv) Relief was to be found for the aged and impotent, whether by alms or by work on the provided stock of Hemp Wool and so forth; poor children should be apprenticed; any parish might build “Houses of Dwelling” for the impotent poor..

(v) Immediate responsibility lay on the Parish overseers, though the Magistrates were responsible for their appointment and activity. The area for relief was the individual’s native place, or usual place of work.

(vi) But in aid of a poor parish, the Justices might order a rate on the whole neighbourhood.

In Norfolk, about 500 children a year were apprenticed. Not merely was relief made a public duty but the government insisted that, however it was done, work must be found for the workless. However, there was passive resistance and selfishness from some Squires. By the late 18th. century, Workhouses and, so called, Gilbert Union Houses of Industry, named after an Act of Parliament, had been introduced and one such was situated in Melton Constable, which included Brinton within its area of responsibility. Perhaps Sharrington, with its Lordship and farms was rich enough to look after its own poor.

Textile Manufacture in Sharrington.

In East Anglia, a commercial textile industry developed in the Middle Ages. The production, for outside markets, of both Linen made from locally grown Hemp and Worstëad (wool) in Norfolk goes back to, at least, the 13th. century and possibly much earlier. In the 17th and 18th. centuries, linen manufacture continued, but it only produced cheap quality cloth for local markets. About 6 to 10 weavers are known to have produced linen in Sharrington during these times but, by 1840, all textile manufacture had virtually ceased in Norfolk owing to the competition of factory produced cottons.

Source References:

(i) A History of England,

(ii) An Historical Atlas of Norfolk.

The 18th. Century and Mrs. Jodrell’s Map.

The first map of Sharrington, of any accuracy, that we have, is the Estate Map prepared by Mr. C.Bell for Elizabeth Jodrell, widow, of 1784, being the estate owner at that time. Although mainly interested in her own holdings, the map does show most of the buildings and plots of land as they were situated at that time and, therefore, already in existence before 1784. (See Appendix II).

Sharrington Hall and Daubeney Hall Farm

During the tenure of the Daubeney Lords, the old manor house is believed to have been called Daubeney Hall and, during that period, probably in the 15th. or 16th. Century, Daubeney Hall Farm would have been built, which was probably the residence of the Estate Farm Manager. However, in 1784, the farmhouse and the land behind was in the residence of the Reverend Mr. Cory, so the farm may have passed out of the estate’s ownership.

Hunt Hall and Hunt Hall Farm

Sharrington Hall had passed from the Daubeneys to the Hunt Family by 1601 and William Hunt was Lord of the manor. In 1645, on an inquisition of lunacy, it was found that Margaret, widow of William Hunt, son and heir of Sir Thomas Hunt, was a lunatic and “seized for life the manors of Sharrington, Holt Hayles, Geyst and Wichingham. Thomas Hunt, Gent. was her son and heir and married to Anne, daughter of John Sherwood”. It was possible that sometime in the 17th. century, Hunt Hall Farm was built. However, by 1768, the Freeholder of Hunt Hall Farm was William Bangay. In 1806, a William Bangay was the occupier but not the owner of the property, which was owned by Francis Mann of Thornage, a member of the Bangay family. Hunt Hall Farm was in the occupation of the Bangay family until 1868.

After the Hunt family, Sharrington Hall was conveyed to Mr. Newman Gent., whose son and heir, William Newman Esq. was Lord and High Sheriffof Norfolk in 1702, and Patron of All Saints Church. By 1720, the estate had passed to Richard Warner Esq. of Elmham and by 1758 to the Jodrell family.

Other Old Buildings

There are a few other old buildings still standing which are shown on Mrs. Jodrell’s map, for example, The Barn, opposite Sharrington Hall, marked Barn Yard, now converted into private dwellings. The Swan Inn, Holt Road and The Chequers Public House, Bale Road, now both in private occupation. Stiles Farmhouse, covered in more detail later. There may be other buildings still standing since 1784, but it is difficult to tell from the map, as it is mainly concerned with Mrs. Jodrell’s property. Also, more modern buildings may have been built on the same sites.

Stiles Farm.

This farmhouse is considered in some detail, as it forms an interesting and significant section of the history of Sharrington. Stiles Farm is situated on the corner of The Street and Hall Lane. It is, like all the old buildings in Sharrington, of flint construction and it has a well sunk in the front garden. The first record of Stiles Farm and the land behind is from 26th. July 1654, when, according to The Court of Sharrington Manor, it is a “Copyhold Estate”, the definition of which is “a species of estate or right of holding land according to the custom of the manor, by copy of the roll originally made by the Steward of the Lord’s Court”. The holder of the Messuage (a dwelling with the adjoining lands appropriated to the household) at that date was John JUDE and Jane, his wife. Therefore, Stiles Farmhouse was built before 1654.

On 26th. July 1654, JON”‘ Jude surrendered “the messuage and one acre with Brinton Close of Five Roads” to Robert Burton Gent. Brinton Close of Five Roads, from Mrs. Jodrell’s map, would appear to be what is known as Lower Sharrington, but is now, generally thought of as part of Brinton. If you walk down the hill from Sharrington towards Brinton, at the place where the little lane forks off to the right, that is the commencement of Brinton Close, being enclosed by five lanes (roads) at that time, with the stream running through it and part of Sharrington Parish.

On the 15th. October 1680, during the reign of Charles II, the property was surrendered to Thomas Moore, who died andwas buried in Sharrington Churchyard on 9th. August 1699. Thomas left the property to his wife Hester and his daughter Anne, wife of Edmund Girdlestone. In 1743, Thomas Girdlestone, son and heir of Anne, obtained the property, then there is an extraordinary record. “It was the time at which the cottage and grounds were obtained freehold by a fraud against the Manor Estate”. However, there is no explanation of this. In 1745, the property seems to have been divided within the family, part of which inherited and occupied 5 Road Croft, Brinton Close.

On 4th. October 1751, Robert Spencer, Yeoman, and Anne, his wife, daughter of Thos. Girdlestone, were the owners of Stiles Farm, which was in the occupation of the Widow Williamson ? In 1765, Robert Spencer left the property to his son, also named Robert. This Robert, who was a miller of Briston, sold the property to Robert Sharpin, farmer of Thurning, and Jos. Woodcock, Grocer and Draper of Brinton, butthe cottage was said to be in the occupation of Joseph Dennis. On 10th. January 1801, the property was sold to the Jodrell Estate for £250 by Robert Sharpin. So Stiles Farm returned to the ownership of the Sharrington Manor, then part of the Salle Park Estate, and it remained so with various tenants until sold to private ownership in the 20th. century.

Buildings Demolished Since 1784.

As previously stated, there were no buildings on the north side of, what is now, The Street in 1784, except for buildings on the Holt Road towards the direction of The Swan Public House. There never were buildings north of The Street as this was Sharrington Common or The Common Sheepwalk. On Mrs. Jodrell’ s map, there are three buildings shown on the south side, to the east of Stiles Farm, alongside land marked “Shepherds Pightles”. Two of these buildings were, most probably, shepherd’s dwellings and marked as being owned by the Estate. These three buildings have long been demolished.

In the field to the east of New Road and The Street, two houses are shown alongside land marked as “Turner’s Pightle”. These premises are also long demolished but, after ploughing, the locations of these properties, marked by flints and bricks are clearly visible. Also, along the east side of The Street, buildings are shown, one probably on the site of the present Village Hall, which has a capped well in front of it. These buildings, and no doubt others, have been demolished.

Stone Cross

There are the remains of a stone column, which has been rebuilt, at the junction of Bale Road and the lane which leads to Sharrington Hall. It is said that it could be the remains of a Pilgrim’s Cross on a route to the Walsingham shrine, but who knows?. In Catholic Countries, as this was at the time it was built, crosses are erected everywhere and many survive in this country in towns and villages.

General History

After the death of Queen Anne in 1714, who died without leaving an heir to the throne, the search was on for a new King. Of course, direct descendants of the Stewarts were alive and well in France, but they were Roman Catholics and unacceptable. The search widened and alighted on a distant relative, GEORG, Grand Duke of Braunschweig and Lüneburg and Elector of the German Empire. Georg became George I, King of Britain, France! Ireland and Hannover. Therefore Britain and the North German State of Hannover were joined as one kingdom, and remained so until the death of William IV in 1837, when the German State could not, by law, accept Victoria as Queen, though her daughter married the King of Prussia and German Emperor. During the reign of the German Georges, the Stewart Pretenders, Old and Young, tried to wrest the throne from the German dynasty. Bonnie Prince Charlie raised an army in Scotland and invaded England, but he got no further than Manchester before he was chased “O’er the sea to Skye” and thence back to France. Sharrington was, of course, too far south to be involved in the fracas. So, we come to the 19th. century, where documents relating to Sharrington are more in evidence.

The 19th. Century

Since 1797, when the Enclosure Acts closed off Sharrington Common, parcelling out Common Land to landowners, Countrywide, not only in Norfolk, and coinciding with the Napoleonic Wars, rumbling discontent had festered between Farmers and Labourers. Norfolk was the most troubled area in Britain for the first thirty years of the 19th. century. Wages were near starvation level. Parliament was dominated by Landowners and Farmers and The Corn Laws were passed which prevented the importation of grain. British corn reached a very expensive 80 Shillings a quarter.

In 1830, there were food riots, with starving labourers attacking corn mills. The most hated were threshing machines, which deprived the labourer of winter employment. Wage meetings and riots are known to have occurred in Binham, Langham, Blakeney, Cley, Salthouse, Kelling,. Weybourne, Bodham and Baconsthorpe. Destruction of threshing and other machines is known to have taken place in the parishes of Holt and Field Dalling. These troubles were the cause of the beginnings of Trade Union activities in 1870.

New Building in Sharrington

In 1784, there were fewer roads or lanes in Sharrington but, according to a Tithe Map, by 1841, the road system had, more or less, been increased to the present layout. Most notably, The Street, then known as Pigg Street, had been lengthened and connected to Hall Lane near. Stiles Farm. The Jodrell Estate had constructed semi-detached farm labourers’ cottages, some of which are still standing and in the occupation of private owners. In Pigg Street, No’s 1 and 2 have been combined into one dwelling. Two other cottages in the centre of The Street have been converted into one dwelling, but No’s 14,15,16,17,18 and 19 are still semi-detached, but now in private ownership. The remainder of the series of Farm Workers’ cottages have been demolished.

It is not known why the White Family, when they acquired the estate, altered the dates on the front of the cottages to the 1870’s. Also, early in the 19th. Century, several dwellings were built on the north side of Pigg Street, near to New Road, on what had been part of The Common Sheepwalk. Although some of these buildings have been demolished, three dwellings, Well Cottage to Flint Cottage are still standing and in private ownership.

The Census of 1851 and the Occupations of Villagers.

In 1851, a Census was held, the details of which are at Saxlingham. 262 souls were counted in Sharrington and, as far as can be made out, they consisted of the following:‑

In Blakeney Road – Henry MAY, Boot and Shoe maker, living with his wife Rhoda, 3 children and Mary A. GOWER,12 years, Servant.

Hunt Hall Farm – William BANGAY, Farmer, his wife Elizabeth, Martha GIBBONS, 12 years old and Wm. RAYNER, Agricultural Lab.

Holt Road – John RISBURY and wife Elizabeth, both 69 years old and described as Paupers.

Holt Road – Mary GOWER, Widow, .62 years, Pauper.

Holt Road – John BAMBRIDGE, Agricultural Labourer, wife Mary., 2 sons, 1 daughter and 2 grandchildren.

Holt Road – Richard BANGAY, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 2 daughters, 2 sons, 1 grandson and 1 Lodger.

Holt Road – Mary MORE, Widow, Charwoman, 2 daughters, 2 sons, one of which was Joshua, 14, Errand Boy.

Holt Road – Henry WOODROW, Ag. Lab., wife Ann, 5 daughters, 1 son.

Fakenham Road – James TURNER, Joiner, wife Emely, 3 sons, 2 daughters, Lucy, 9, Scholar.

Fakenham Road – Robert RISBOROUGH, Ag. Lab., wife Harriet, 1 son, 1 daughter and Robert RANSOME, Lodger.

Holt Road – James BARNS, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 4 daughters, 4 sons. Holt Road – James WATTS, 81, wife Christiana, 63, Paupers.

Old Hall ? – Christopher WEST, Farmer, wife Alice, Martha MUNDHAM, House Servant, Mary PLATTEN, Dairy Servant,

John PINCHIN, Groom.

Swan Inn – John TURNER, Farmer and Beer Retailer, wife Hanah.

Daubeney Hall – Jonathan MAY, widower, 60, Farmer, ? WOODS,

6 year old girl, Lodger. ? ? 36 year old Woman Servant.

Belawes Church Farm – William MARNER, Farmer, wife Elizabeth, Lucy BAMBRIDGE, House Servant, Wm. SMITH, Farm Lab.

Brinton Road – Farwell CORK, 75, Ag. Lab., wife Lydia.

Chequers Inn – Charles GIDNEY, Innkeeper, wife Rachel, 2 daughters, 4 sons,

Mary BANGAY, 57, Children’s Nurse.

– Thomas TUCK, Ag. Lab., wife Ann, James BANGAY,9, visitor, Scholar.

Glebe House – Mark WATERSON, Ag. Lab., wife Elizabeth, 3 sons,

1 daughter unmarried, married daughter Ann MIDLETON and husband James MIDLETON, Ag. Lab., 1 son.

Church House (Farm?) – William ARNOLD, Farmer, wife Jane, Sarah LOOSE, House Servant.

Lower Sharrington – John HOWARD, Farmer, wife Ann, James ROBERT,6, grandson, Scholar, One 72 years old Widow, Lodger.

Lower Sharrington – James BIRD, 75, wife Ann, 73, Paupers, John WOODROW, Lodger.

Lower Sharrington – Wm. FRAZIER, Ag-. Lab., wife Margaret.

Lower Sharrington —James THASPEN, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 1 son,

2 daughters, Ann, 76, Mother-in-Law, Pauper.

Lower Sharrington – Wm: GYMES, Labourer, wife Hanah, 1 daughter, 4 sons.

Stone Bridge – Edward BULLEN, Shepard (Shepherd 7),. Mary, Shepard’s Wife, 2 sons, 3 daughters, Robt. CLAXTON, Lodger.

Pitt House – Wm. TURNER, Carpenter, wife Mariah, 3 daughters, 3 sons.

? – Joshua MORE, 83, wife Ann, 86, Paupers.

? – Robert CARMAN, Farming Bailiff, wife Rachel, 2 daughters, 3 sons.

? – Henry CHATTEN, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 3 daughters, 1 son, Mary NEAL, Mother-in-Law, Pauper

– William LEE, 67, Ag. Lab.

? – David MAY, 35, Boot Maker.

Pigg Street – Francis SHARPEN, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 2 sons, 2 daughters.

Pigg Street – James GOWER, Ag. Lab., Mariah HURN, Housekeeper, on Simon.

Pigg Street – Simon GOWER, Farmer, Elizabeth, 95, Mother, Damila NOCKLES, 71, Sister.

Pigg Street – Edmund NEAL, Ag. Lab.,. wife Ann, 5 sons, 2 daughters.

Pigg Street – Samuel Goldsmyth LAKE,- Groser (Grocer?) and Draper, wife Elizabeth.

Pigg Street – Ann MAY, 74, Widow, Pauper.

Pigg Street – William NEAL, Ag. Lab.,wife Susan, 2 daughters, 3 sons.

Pigg Street – John MUNDHAM, Pauper, son John, Farmer’s Lad, 2nd. son, daughter Margaret, Scholar.

Pigg Street – Robert SHARPEN, Keeper, wife Susan, 3 daugh. 2 sons. Pigg Street – Robert CLARK, Carpenter, wife Ann, 3 daugh. 2 sons.

Pigg Street – John WHITE, Farmer, wife Elizabeth, 3 daughters 2 sons, Laurence ?, visitor.

Pigg Street – Martha EYON, widow, Seamstress, son Joseph, Fm. Lab.

Blags House – William CLARKE, Machine Seedsman, wife Ann, son Martin, Apprentice Blacksmith, 1 other son, 7 daughters.

Pigg Street – Meriah WARNS, Ag. Lab.’s wife, 2 sons, Elizabeth SHARPEN, sister.

Pigg Street – William SHARPEN, Ag. Lab., wife Pheaby, 4 sons,

1 daughter, Esther SHARPEN, Aunt, Needlewoman.

Lower. Sharrington – Richard WARNS, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 2 sons,

2 daughters, William WARNS, 84, Father, Pauper.

Lower Sharrington – Sarah SKILLINGS, widow, Pauper; 3 sons, 1 son,16,Ag. Lab., son, 14, Farm Lad, 1 daughter.

? – Henry NEAL, Ag. Lab., wife Mary, 2 sons, 3 daughters.

? – We end with poor. Phebe CLARK, widow, Pauper. (and we don’t even know where she lived!).

At that time, 1851 – 1853, “The Parish comprises about 864 acres, chiefly the property of Sir R.P. JODRELL, who is Lord of the manor and Patron of the Living. Here are the ruins of an Ancient Cross. (Note: Glebe House is shown as occupied by an Agricultural Labourer, but “Glebe” is Church

Property, shown on the 1784 map as being at the corner of Bale Road and Brinton Road,, where there used to be the Rectory, so, at that time, it would appear that the Rector lived elsewhere?) It would also seem that Church Farm and other property in the vicinity of The Chequers Public House were built early in the 19th. century, but not the old barns near the church, which are probably older and which have been converted into private dwellings.

In 1896, the Lord of the Manor and Chief Landowner was Major. Timothy WHITE of Sall (Salle) Park, in the church of which the family is commemorated and buried in the churchyard. The Chief crops at Sharrington were wheat and barley. The charities, amounting to about £10 yearly, were for clothing. (no doubt for the Paupers living in the village). The village was 3 miles north of Melton Constable Junction Station on the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway. By this date, the north and south aisles of All Saints Church had been demolished and the walls of the nave patched up. (The church spoilt according to one account). The bell tower contained one bell dated 1715. Near the church stood the base and part of the shaft of a stone cross. The Parish was under the Briningham United District School Board and the children of Sharrington attended the school house at Brinton.

Citizens of the time were: Rev. Charles BRUMELL M.A.

living at the Rectory. William ALLISON, Fish Hawker. Thomas Robert DRAKE, Dealer. Willm. GREEN, Farmer, Hall Farm.

James HALL, Farmer. George LAKEY, Farmer. Wm. LAKEY, Cow Keeper. Wm. NEAL, Shopkeeper. Baker. B. PHILLIPO, Chequers Public House. Wm. John POINTER, Farmer and Swan Inn. Wm. SANDS, Farmer.

Chas. TURNER, Farmer. James WARNES, Fish Hawker,

Frederick W.H. WRIGHT, Farmer and Horse Dealer.

By 1916, The Rev. George BUCK was Rector. William

ANNISON, Swan Innkeeper. Wm. John GILHAM, Farmer. Wm. B. GREEN, Farmer. Halt Farm, resides at Warham. Henry LAKEY, Farmer. Samuel PYGALL, Farmer. John RICHMOND, Farmer Church Farm. Robert John SANDS, Farmer: Chas. TURNER, Farmer James WARNES,

Fish Hawker. Chas. Wm. WRIGHT, Chequers Innkeeper.

It was now into the third year of the Great War and, although farming was a reserved occupation, no doubt many of the young lads of Norfolk had answered Kitchener’s call to join his new army. One such, though not a young lad was, probably, the poor chap who now lies in his war grave in All Saints Graveyard.

The War Grave Headstone reads, “14969 Private E. BAMBRIDGE ESSEX Regiment, died 29th. July 1917, Aged 31”. In the Census records of 1851, we read of John BAMBRIDGE and his wife Mary, living in Holt Road, Sharrington, at that time, maybe Private E. BAMBRIDGE was their grandson?. It is not usual to find an isolated war grave in a churchyard in England, the reason being that soldiers killed in the Great War were usually buried in France or Belgium in the hundreds of War Grave Cemeteries in those countries.

If a soldier was wounded, he was usually placed in one of three categories: Seriously wounded, likely to die, when he was kept in France or wherever: Lightly wounded, when he would be kept in the Military Hospital in France and, on recovery, returned to his Unit, probably after sick leave: Or “A Blighty”, seriously wounded though likely to recover, when he would be .sent to hospital in England. Edward, Edwin? BAMBRIDGE probably received a Blighty but, unfortunately, did not recover. At least his poor family could visit his grave in Sharrington.

The White Family still owned the estate, but, with the developments in farming, the machines began to take over from horse drawn ploughing and reaping. Fewer farm labourers were needed until, later in the 20th. Century, a very few skilled men in large machines could do the work that had required dozens of men in the not too distant past. The Estate sold all the estate houses into private ownership and, eventually, the agricultural estate itself was sold to a private company. Earlier in the century, the Parish was amalgamated into the Brinton Parish Council, so the Sharrington Parish no longer exists. Sharrington Village has seen some modern development; starting with the erection of the Village Hall in 1953 but, generally, further development has been sympathetic to the character of the village, which has been declared a Conservation Area and is unlikely to be altered much in the forseeable future.

To complete the story, we have seen the village progress from sheep herding and ox ploughing, through invasions, imposed foreign lordships, civil strife and poor conditions for most people. Change was inevitable, but who can say that it was better then than now?

End of Story.

Appendix I.

Lords of the Manor of Sharrington. Dates Known when Held. Sovereigns at the Time.

1066, Beruite of Sharrington belonged to the Kings Manor of Fakenham. King Edward “The Confessor”. King Harold.

1066 Beruite transferred to the King§ Manor of Holt. King William I, “The Conqueror”.

1218 Gregory de Sharenton. Henry III.

1228 Peter de Sharington. (During the Lordships of Gregory

and Peter, the Earls of Clare were the Capital Lords).

1288 Peter de Letheringset. Edward I.

1323 Sir? John Dawbney de Broughton. Edward II.

(Another document names him William Dawbney de Broughton).

1349 Robert Dawbney de Broughton. Edward III.

1364 William Daubenye. Edward III.

1382 (Edmund de Mortimer, Earl of March, was Capital Lord). 1389 William Daubeney de Sarnyngton. Richard II.

1399 (Roger de Mortimer, Earl of March was Capital Lord).

1403? Thomas, son of William Daubeney. Henry IV.

1433 William Dawbney, son of Thomas. Henry VI.

1486 Thomas Dawbney, (Married Anne Warner) Henry VII. 1533 Henry Dawbney, (Married Joane Lomner) Henry VIII.

1565 Christopher Dawbney, (Married Philipa Roberts) Elizabeth I. 1587 Henry Dawbney. The last Dawbney to hold the Lordship. 1601 William Hunt. Elizabeth I

1645 Thomas Hunt, Gent. Charles I.

16 ? Mr. Newman, Gent.

1702 William Newman, High Sheriff of Norfolk. Queen Anne.

1720 Richard Warner, Esq. of Elmham. George I.

1758 Elizabeth Jodrell, Widow. George II.

1853 Sir R.P. Jodrell Victoria.

1896 Major Timothy White of Sall Park. Victoria.

© Peter Chapman – Sharrington